Systematization of an Educational Experience of Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation:The Collective Memory built with Participatory Virtual Tools

Sistematización de una experiencia educativa de apropiación social de la ciencia la tecnología y la innovación:La memoria colectiva construida con herramientas virtuales participativas

JULIO EDUARDO MAZORCO SALAS1

LAURA YAMILE HENAO MORALES1

ROBINSON RUIZ LOZANO2

LIZ ANDREA VARÓN MATHA1

1Universidad de Ibagué, Colombia

2Universidad del Tolima, Colombia

Abstract

The objective of this research was to construct the collective memory of a socio-educational intervention process from the perspective of the different educational actors, students, teachers, and community leaders. For this purpose, a critical epistemological approach was used, a qualitative methodology within the framework of the approach of systematization of experiences and methods of construction of collective memory such as timelines. This methodology was developed in the context of a pandemic during the year 2020 and required adaptations in the instruments and forms of data collection. Findings show the significance of collective experience in terms of moments of reception of physical spaces and elements for the development of science, technology and innovation, as well as the importance of participation in local processes of identification and solution of their own problems, and the relevance of work in and with the community.

Palabras clave: systematization of experiences; collective memory; social appropriation; science, technology and innovation.

Resumen

El objetivo de esta investigación fue construir la memoria colectiva de un proceso de intervención socio-educativa desde la perspectiva de distintos actores educativos, estudiantes, docentes y líderes comunitarios. Se realizó un abordaje epistemológico crítico, una metodología cualitativa en el marco del enfoque de sistematización de experiencias y de métodos de construcción de memoria colectiva, como las líneas de tiempo. Esta metodología fue desarrollada en contexto de pandemia durante el año 2020 y requirió de adaptaciones en los instrumentos y las formas de recolección de información. Los hallazgos dan cuenta de la significatividad de la experiencia colectiva en cuanto a momentos de recepción de espacios físicos y elementos para el desarrollo de la ciencia, la tecnología y la innovación, así como la importancia de la participación en los procesos locales de identificación y solución de sus propias problemáticas y la relevancia del trabajo en y con la comunidad.

Keywords: sistematización de experiencias; memoria colectiva; apropiación social; ciencia, tecnología e innovación.

This article is part of a macro project entitled Systematization of an experience of social appropriation of CTeI to promote critical thinking in students of the department of Tolima. In this project, an agenda was designed for the production and socialization of results of diverse scope and dissemination purposes. Thus, two strategies for dissemination of results were generated. The first, of participatory socialization and validation, with virtual spaces for the presentation of results, participatory design of a results web page, applications, the use of a page on the social network facebook (https://www.facebook.com/ExplorandoAndoCTeI/) and one book in Spanish that collects the experience of the project (Henao, Mazorco-Salas, Pedreros, Ruíz & Varón. 2022). The second was a strategy of academic dissemination of results, including two papers in international scientific events, one research book chapter (Henao, Mazorco, Ruíz. 2021) and the present article presented in English in a Latin American journal, whose purpose is to broaden the scope of the process of co-production of knowledge and dissemination of results. This article, then, presents the findings of an experience systematization process from the perspective of students, teachers and community leaders of schools from 11 municipalities of the department of Tolima, in Colombia, who participated in a project of Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation (CTeI) in their territories. In this document you will find information on the general framework of said project, the social appropriation of the CTeI in Colombia, the approach to systematizing experiences, the methodology used and the results from actors involved.

Education, science and society are three elements that are related on the basis of social appropriation of knowledge and innovation. On one hand, education allows the development of competences that citizens need to be an active participant in society, a role that allows them to freely perform in contexts in which they participate. On the other hand, science, technology and innovation are processes that allow, through the search for validity, to bring citizens closer to better living and development conditions. However, such tools regarding CTeI and complemented with cultural, popular and ancestral knowledge, are not available to citizens, given the little popularization (Colciencias [Colombian Development Institute for Science and Technology], 2010) that they have had. Therefore, the challenge that actors of the educational system, the CTeI and society must address is to achieve the democratization of knowledge, through its social appropriation, because according to Colciencias (2010), there emerge capacities which effectively generate social and economic development for good living in the territories.

“Explorando – Ando” [EA – “I am – Exploring”], is the name given to the implementation of the CTeI strategy in educational institutions in the department of Tolima in Colombia; the educational intervention was carried out in 11 municipalities, and in 166 educational centers; of which, 80% were found in rural areas, mostly far from urban areas, with deficiencies in infrastructure and elements towards the teaching and development of science, technology, and innovation. Adverse contexts challenged by strengthening the social appropriation of CTeI on behalf of educational communities. This framework project involved four axis: the strengthening of participatory capacities for CteI, solutions in CTeI for the development of critical and creativity thinking and communication of the CteI, mechanisms for the exchange and transfer of knowledge of the CTeI and a knowledge management system of the CTeI. At the time the present systematization of the experience was carried out, in 2020, axis one and two and part of four were developed. Both the systematization process, and axis three, have had to face the challenges of remote work in the context of a pandemic.

Within the framework of a project linked to citizen participation and social appropriation of the CTeI in the educational institutions of the 11 targeted municipalities of the department of Tolima, the question of collective memory becomes pertinent, owing to the experiential nature of the program, the social intervention nature of the implemented program, the conception of social appropriation as a broad purpose of the project around the development of capacities installed in the territories and the recognition of the suitability of knowledge transfer the project has. Each one of these elements accounts for a dimension of relevance of the construction of collective memory for the project: the collective memory of experience, significant moments, learning, challenges, difficulties, transformative milestones, and science and technology tools of what residents are able to tell other residents per territory.

Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation

In the last two decades, the Social Appropriation of the CTeI (ASCTI) in the Colombian and Latin American context has been a booming issue within the framework of public policies of different countries of the region. Colombia, a pioneer in this aspect, establishes through Law 29 of 1990 and Decree 585 on February of 1991 the mission of Colciencias, that raises the need to design and implement various ASCTI strategies in Colombian culture. Subsequently, in 2005, the ASCTI National Policy linked elements associated with the principles of the knowledge society and the challenges of appropriation around the use and insertion of this knowledge in the country. Then, in 2010, the National Strategy for the Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation was created, with which a precedent was set in the country. Said strategy is based on four axis of action: citizen participation, communication, transfer and exchange of knowledge and management for appropriation (Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation Colciencias, 2010).

On the other hand, countries such as Bolivia, Chile, Cuba, Ecuador, Spain, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela have been implementing ASCTI on the agenda of their territories through various programs and initiatives attached to the Andrés Bello Agreement (CAB, Ministerio de Educación, 2019). in which the international intergovernmental organization aims to contribute to the development of the member countries through the generation of consensus between culture, education, science and technology. This is how in 2013 the V Meeting on Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation of the CAB was held in Ixtapan de la Sal, Mexico, with the participation of Colombia, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic and Mexico. The objectives of the meeting were:

Establecer un balance regional sobre la implementación de políticas y estrategias en el tema, en los países del CAB; e identificar y proponer opciones de trabajo conjunto entre los países, que favorezcan el fortalecimiento de la Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación (ASCTI), a través del intercambio de buenas prácticas y el desarrollo de proyectos conjuntos. [Establish a regional balance on the implementation of policies and strategies on the subject, in the CAB countries; and identify and propose options for joint work among the countries that favor the strengthening of the Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation (ASCTI), through the exchange of good practices and the development of joint projects.] (V Reunión en Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación de los países CAB, 2013, p.7).

As a result of said meeting, five agreements that arise as a joint work agenda were made. One of this agreements proposes the Systematization of Experiences (SE) of the initiatives carried out in the different countries, since they propose that “una parte importante del fortalecimiento de la ASCTI es el reconocimiento de las experiencias y de los aprendizajes que tienen los países en el tema” [An important part of strengthening ASCTI is the recognition of the experiences and learning that the countries have on the subject] (V Reunión en Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación de los países CAB, 2013, p.37). To do this, the systematization of one or two experiences per country, plus the international publication and distribution of a book for each experience, was proposed. (V Meeting on Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation of CAB countries, 2013).

On the other hand, in 2014 the V Forum of ASCTI was held in Bogotá, Colombia, in which various actors participated, such as the Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation-Colciencias, from the group of Social Appropriation of Knowledge (ASC). The Knowledge Management work table made a comprehensive recommendation for the ASCTI Strategy, consisting of three axis, in which one of them talks about systematization from the perspective of the actors involved. This document proposes that the evaluation shall have a participatory approach. It was suggested that the process:

No se realice desde el afuera, ni por factores que generalicen, sino que los mismos actores que están participando se involucren en los mecanismos de sistematización de su proceso. Esto implica la heterogeneidad en las metodologías de seguimiento y evaluación de los procesos de apropiación. [Is not carried out from the outside, nor by factors that generalize, but rather that the same actors who are participating are involved in the systematization mechanisms of their process. This implies heterogeneity in the methodologies for monitoring and evaluating appropriation processes.] (Memorias del V Foro de Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación, 2014, p.153).

The systematization of experiences is pertinent as a research methodology for projects related to ASCTI and educational experiences, such as learning, pedagogical practices, the perception of educational actors, the educational community and the territory and collective memory. This is because the Social Appropriation of Knowledge (ASC), when seeking the democratization of the knowledge itself (De Sousa, 2010), aims to socialize knowledge of CTeI that has not been historically equitable, and access to it has been variable according to territory and social, economic, environmental, and cultural dimensions.

Systematization of Experiences

Systematization as a research methodology is a process of historical recovery that promotes scenarios of search, ordering, reflection, criticism, analysis, interpretation and construction, conducive to the development of knowledge, its communication, and consolidation of pedagogical practices around the educational attention of populations, with a clear transformative intention.

Luisa Mercedes Vence (2014) grants to the “systematization of experiences” a series of characteristics, which deserve relevance and identification, by pointing out that “es una práctica concreta porque se sitúa en un espacio y tiempo determinados, desarrollando acciones y actividades identificables” [It is a concrete practice because it is located in a specific space and time, developing identifiable actions and activities.] (p.3); that it is systematic insofar as “sus acciones llevan un orden lógico, guiado por un principio de organización interna (actividades, secuencia, metodología) establecido por el líder de la experiencia y/o sus participantes” [Its actions have a logical order, guided by a principle of internal organization (activities, sequence, methodology) established by the leader of the experience and/or its participants.] (p.3); that it is “evidenciable al conseguir sus objetivos y poseer mecanismos para demostrarlo” [evident by achieving its objectives and having mechanisms to demonstrate it] (p.4); that it is self-regulated to the extent that it “analiza y reflexiona sobre su desarrollo identificando sus fortalezas y oportunidades de mejora” [analyzes and reflects on its development, identifying its strengths and opportunities for improvement] (p.4), and that it is “contextualizada porque planea sus acciones en estrecha relación con el medio cultural, social, político y las necesidades de desarrollo de la comunidad educativa a la cual atiende” [contextualized because it plans its actions in close relation to the cultural, social, political and social environment, and the development needs of the educational community it serves] (p.5).

On the other hand, Barbosa-Chacón, Barbosa-Herrera & Rodríguez (2015), carried out a meticulous study of the structure of the conceptualization of the “systematization of experiences”, categorizing its definition based on the various objectives, actors and factors that are related to it and that energize each other. Therefore, it is considered interesting to provide a reflective look at the authors’ proposal, and understand that this concept could be multifactorial depending on the intention, object and methodology proposed by the researchers. These processes are part of the self-reflection, understanding and transformation of social and educational practices, and especially of those actions that are part of everyday life and personal, collective and institutional realities.

Therefore, systematizing significant experiences in the educational field is an intentional investigative act that promotes, in first measure, the registration of school practices that represent the various educational actors greater impact and/ or meaning, to later systematize them, and that their socialization constitutes a relevant contribution, both in learning and in the transformative potential that the actors involved, as well as other local, regional and national educational institutions, embody for their immediate environment. This way, the systematization of experiences as a methodological proposal for the understanding, review and analysis of said experiences, emerges as a different alternative:

A las formas tradicionales de comprender la investigación y la producción de conocimiento científico en Occidente, cuya descontextualización histórica y pretensión de ser universal, ha estado al servicio del colonialismo y la globalización capitalista, invisibilizando otras formas de entender el mundo y la vida, y excluyendo a los sujetos que las producen. [To the traditional ways of understanding research and the production of scientific knowledge in the West, whose historical decontextualization and claim to be universal, has been at the service of colonialism and capitalist globalization, making other ways of understanding the world and life invisible, and excluding to the subjects that produce them.] (Jara, 2012, p.56).

The systematization of experiences emerges in Latin America from the effort and need to build “marcos propios de interpretación teórica desde las condiciones particulares de nuestra realidad” [own frameworks of theoretical interpretation from the particular conditions of our reality] (Jara, 2018, p.27), evolving and transforming since the sixties, closely linked to the popular education and participatory action research, product of the cultural, political and social movements that took place throughout the continent, especially in the Southern Cone with the Popular Unity Government in Chile and later in Central America with the Sandinista Revolution.

From these experiences, the Alforja Network emerged in 1981 in Central America, made up of various civil organizations from countries such as Guatemala, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras and Panama, whose experiences are identified from the beginning with “procesos de educación popular, con organizaciones y movimientos de la región mesoamericana, en diferentes coyunturas, (aportando) a procesos emancipatorios como parte de su compromiso sostenido para la región” [popular education processes, with organizations and movements of the Mesoamerican region, at different junctures, (contributing) to emancipatory processes as part of their sustained commitment to the region] (Red Alforja, nd, sp). This organization would be crucial for the systematization of experiences as a methodological proposal as a result of the increasingly growing movements throughout the continent on issues related to educational innovations, civil, political, economic, social, cultural and environmental rights, “como fue el caso de los comités de Justicia y Paz de Brasil, la Vicaría de la Solidaridad de Chile, la Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos de Ecuador, el Servicio Paz y Justicia y las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, en Argentina, entre otros” [such as the case of the Justice and Peace committees of Brazil, the Vicariate of Solidarity of Chile, the Ecumenical Human Rights Commission of Ecuador, the Peace and Justice Service and the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, in Argentina, among others] (Jara, 2018, p.45).

Since then, various Organizations, government entities, academic actors and even cooperation agencies have contributed to strengthen and validate the systematization of experiences as a current way to understand and produce knowledge from the territories while its actors reflexively propose and take charge of their reality. Some examples of organizations that have emerged in the last decade and that make use of the systematization of experiences as an investigative tool are the Permanent Systematization Workshop of Peru, the Educational Dimension in Colombia and the Virtual Library of the Latin American Program to support the Systematization of the Council of Popular Education of Latin America and the Caribbean (CEAAL) (Jara, 2017).

Systematized Experiences

The use of this methodology has favored social processes in fields such as social organizations, education, research and emerging environments. Publications in the systematization of experiences have been developed with axis of political organization, identity and memory (Chimbo, 2019); human rights in older adults (Cuello-Lacoutire and Jaramillo-Jaramillo, 2021); local initiatives against climate change (Bhat, 2014); local community development process (Herout, 2015); good governance (Echeverry-Velásquez and Prada, 2021); memory and social reconciliation (Corredor-Sotelo and Fuentes-Fuentes, 2021) and community public health processes (Peña-Varón, Marín-Velásquez and Mosquera-Becerra, 2021).

Furthermore, there is evidence of the application of the systematization of experiences in educational environments, in didactic issues (Díaz, 2019), constructivist training processes (Quispe, Álvarez, Mancilla, Acarapi and Navia, 2018); subjectivities of teachers (Mora-Lemus, 2021); teaching and rurality (Rivera and Valencia, 2016); scientific inquiry processes (Honor, 2015); construction of institutional knowledge in educational institutions and projects (Chuchullo and Cáceres, 2015) (Morales and Quintero. 2015); and popular education (Torres-Carrillo, 2010). The applications of the systematization of experiences expand as well to the field of social work. Linking the systematization of experiences and popular education (Goldar and Chiavetta, 2021; Castañeda-Meneses and Salamé-Coulon, 2021); social work in the context of a Covid-19 pandemic (Sepúlveda-Hernández, 2021); family support programs (Esteban-Carbonell and Olmo-Vicén, 2021).

Related to this research, there are investigations about the relationship between systematization of experiences and CTeI; such as those of Sequeda (2017), which link the CTeI with the processes of the Maloka park in Colombia; likewise, processes of social organization and CTeI by Estupiñán, Mosquera, Mondragón and Vitale (2014) and the relationship between promoter actors and the ASCyT (Pérez-Bustos, 2012).There also are works about the systematization of experiences as a participatory research strategy as worked by Falkemback and Torres-Carrillo (2010) and Torres-Carrillo (2021).

Finally, an innovative proposal stands out, which links the knowledge of research with training and empowerment in social organizations with the systematization of experiences. This proposal is developed by Escuela de Experiencias Vivas del Centro de estudios con poblaciones, movilizaciones y territorios [School of Living Experiences of the Center for studies with populations, mobilizations and territories]. (Agudelo and Jiménez. 2017), (Jiménez and Agudelo. 2020).

Collective Memory and Systematization of Experiences

La dimensión de la memoria colectiva permite que la historia de otros y la historia propia se empiecen a concebir como una historia-en-común [The dimension of collective memory allows the history of others and one’s own history to begin to be conceived as a common-history]. (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, 2015. p. 19.)

Ricoeur (2004), in his text: Memory, history, forgetfulness, asked the question, “Is memory primarily personal or collective?” (p. 125). The author makes the distinction from the emergence of Western thought and its egoic development in modernity as a setting for the construction of individual identity forms and centered on conceptions of isolated subjects. These conceptions are prior to the emergence of the interpretive turn, which gives room to the processes of subjectivation and identity construction in relation to the other. That is, a shift from the construction of identity and memory as individual physical processes of reminiscence, to the construction of identities and collective memories focused on the relationship and recognition with the other (Ricoeur, 1996).

Acevedo (2008) states that: “The recovery of collective memory as an essential component of the systematization of experiences, enables the active and dialogical reconstruction of social reality from the perspective of participants” (p. 8). Collective memory as a category for the systematization of experiences approach maintains an epistemological and methodological coherence. As discussed below, this is shown by the epistemological aspect in terms of being categories that are inscribed in the forms of co-production of knowledge for social transformation, and by the methodological aspect, to manifest itself in qualitative and participatory tools and processes of narrative constructions.

Memory for systematization is understood as an event with transformative potential. The passage of memory from a positivist category to a social category demarcates a transformation that is not only explanatory or comprehensive, but fundamentally transformative. It is about a step from memory as a linear macro story towards memory as a social and political event of life forms in non-sequential, non-hegemonic historical frames. So it is a memory that invites the construction of social possibilities, rather than rote repetition (Halbwachs. 2004).

Collective memory is not by itself. It is the emergence of common narratives embodied in subjects and lived stories. Therefore, collective memory is a co-construction, a fabric of meanings around common experiences, without any claim to truth or unification, without homogenizing the subject or resolving tensions in the standardization of memory. This notion thus takes the form of a process of subjectivation and identity construction, establishing from there a link with the past in its reconstruction, with the present in its sense of event and with the future in the political commitment to social transformation. In this way, the role of collective memory in the processes of systematization of experiences is transversal, not as a product to find or discover, but as a narrative on which its co-construction must be promoted.

In this way, the participation of people involved is essential for the systematization of experiences. In this regard, Acevedo (2008) states that “la fuente de conocimiento se fundamenta en los recuerdos individuales, tradiciones orales, archivos documentales, el territorio, los objetos y fotografías, las cuales posibilitan recuperar tanto la experiencia vivida desde la perspectiva de los participantes del estudio” [the source of knowledge is based on individual memories, oral traditions, documentary archives, the territory, objects and photographs, which make it possible to recover the experience lived from the perspective of the participants of the study] (p. 9). It is with voices and narrated stories that common meanings are built. An oral and decision-making real participation is not merely representative. This requires methodologies and instruments for the construction of collective memory, centered on participation and open to instruments and data of alternative narrative expressions.

Method

This research is part of the critical-hermeneutical paradigm (Guba, 1990), because it has a dual purpose: to go through the comprehensive processes of the narratives of the actors involved and to favor processes of awareness and learning from the findings. In addition, reality is recognized as a dynamic historical and social construction and in a constant process of transformation. In methodological terms, it adheres to the systematization of experiences approach as a strategy for the co-production of knowledge and community empowerment based on grassroots social processes (Jara, 2017; Carrillo and Cordero, 2017).

Instruments

The timeline is used as an instrument for collecting information in qualitative methodological approaches, social cartography approaches, memory studies and systematization of experiences. At the same time, it is a tool that can be applied both for individual collection processes, as well as for participatory information collection, which allow dialogues between participants and construction in the practice of categories such as collective memory, as its use in systematization of experiences.

It is a chronological method of reconstruction of subjective meaning in a non-sequential linear organization. It allows to structure and rebuild processes on two levels, one objective and one subjective. The objective aspect is in relation to a linear time frame, such as an experience shared by a group or community. The subjective one consists on the narrative reconstruction of the memory of each participant as a living expression of their processes of meaning construction and attribution of meaning to what was experienced. The latter allows the reconstruction of non-sequential processes, which are expressed in learning or significant moments in the spiral of the construction of a meta-story that, with the input of the experience of subjects, manages to build group and collective panoramas.

The Timeline (LT) instrument was implemented as a tool to analyze and identify significant moments and narratively expressed experiences and learnings for participants of Explorando Ando project, within the framework of its process. This was applied between September 15th and 30th, 2020 in 56 educational centers belonging to 11 municipalities where the project is carried out. By means of the guide sent through pedagogues in the territory, the instruction provided was to identify three or more important moments in the project’s journey and add a brief explanation of the reason why it was done that way. For this, the metaphor of the road was used, which is reflected in the illustration that is exposed in said guide, in which the stops or location points can be identified as those that would be said important moments. Additionally, the possibility of replicating on a blank sheet, extending or appending more space is provided, if necessary. With the accumulation of timelines, researchers could build a meta-story from collective memory about the learnings of the installation of the program in their territories. This meta-story should later be shared with the participants. The instrument sought to evoke two central structures of the notion of collective memory, space and time, as frames on which memory is expressed and collective memory is built. An interactive format that encourages participation was proposed.

The design of the timeline was developed in 5 stages: 1. Design of the instrument based on the categories of inquiry; 2. Design of the application strategy and graphic design of the instrument; 3. Pilot with the team of researchers; 4. Final redesign to adjust wording and vocabulary; 5. Training of the pedagogues of the project, who are the agents in the territory with the closest contact with the participating communities and would serve as guides in case of possible doubts about the instrument. The final instrument can be seen in Figure 1.

Figura 1. Timeline guide given to participants

Due to conditions of physical isolation due to the pandemic and connectivity difficulties in the territories, adjustments were made to the means of application for the instruments. For populations without access to permanent connectivity, guides were designed with instructional work and language adaptations to facilitate understanding and execution from home. Likewise, the answers to the guide were allowed to be made in a different way, according to the resources of each participant. These were sent through WhatsApp to the registered phones of participants, children’s parents, leaders, teachers, and others. Results were received via this application as well. In this way, Whatsapp served as a mean of communication to achieve the participation of different actors in a rural context and with little or no access to internet connection, whose families do not own computers and only have 1 cell phone per family nucleus. These conditions of geographic accessibility, barriers to access to real-time communication media, and the pandemic context generated methodological challenges that the virtual resources, the instructional design of the instruments and the dialogic roles of the researchers contributed to address.

Participants

In total, 166 timelines were received, of which 58 were from students, 47 from leaders, and 55 from teachers. In the municipality of Chaparral, a total of 20 timelines were received (10 students, 4 leaders and 6 teachers), since there was the participation of 6 educational centers with their creativity teams. Meanwhile, 10 (4 students, 2 leaders, 4 teachers) and 12 (4 per role) timelines were obtained respectively from Armero-Guayabal and Melgar; the first one having the participation of 3 headquarters, and the second of 4. For the rest of the municipalities, between 15 and 17 timelines were received, which corresponds to the minimum number of actors (3) on which timelines per creativity team were applied (1 for each headquarter, for a total of 5 per municipality).

As such, the Espinal (4 students, 6 leaders, 5 teachers), Flandes (4 students, 6 leaders, 5 teachers), Líbano (5 students, 5 leaders, 5 teachers), Ortega (5 students, 5 leaders, 5 teachers), Planadas (6 students, 4 leaders, 5 teachers) and Rovira (6 students, 4 leaders, 5 teachers) municipalities received 15 timelines each, while the Lérida (8 students, 4 leaders, 5 teachers) and Saldaña (6 students, 5 leaders, 6 teachers) received 17.

Results

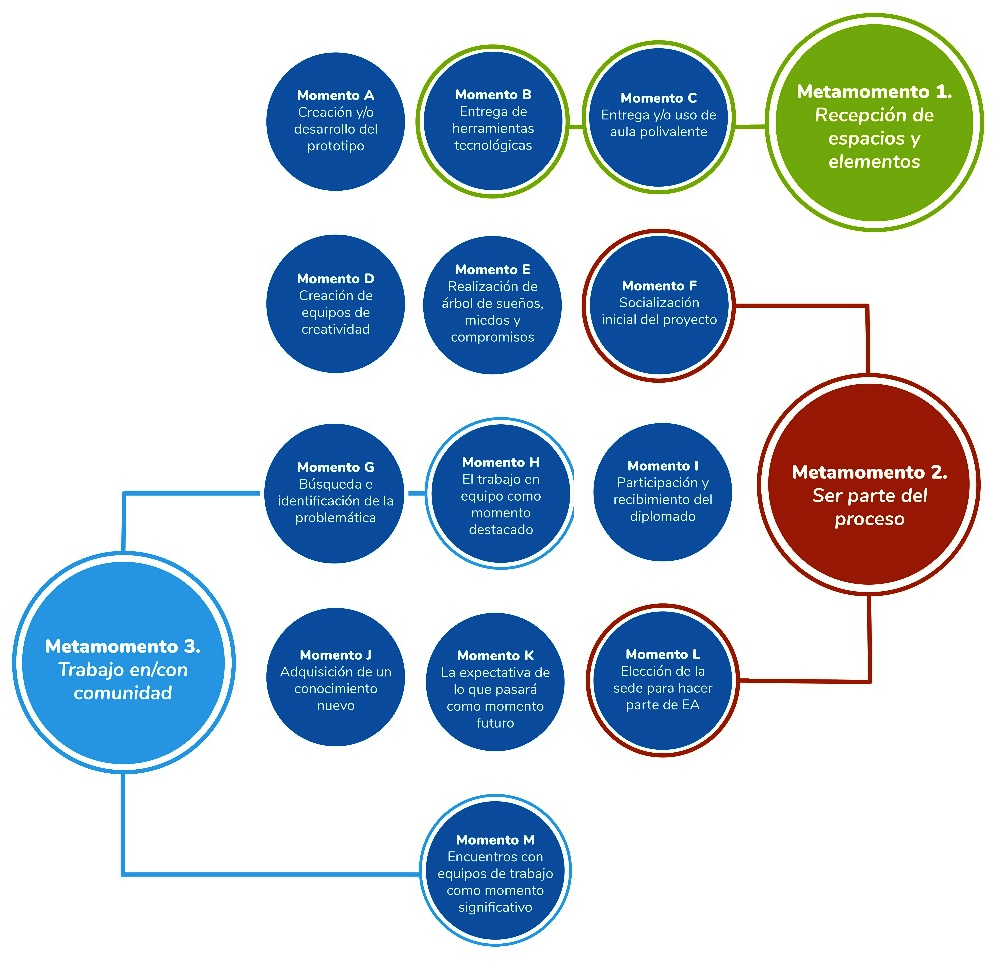

The ATLAS.ti software was used to perform the analysis of the most significant moments that arose through the timelines. 13 moments, repeatedly found in the timelines as significative, were identified, this moments being: (a) prototype creation and/or development (50); (b) technological tools delivery (46); (c) multipurpose classrooms delivery and/or use (39); (c) creativity team creation (35); (e) dream, fear and commitment tree realization (30); (f) project’s initial socialization (30); (g) problem search and identification (24); (h) teamwork as a major moment (15); (i) diploma course participation and completion (14); (j) acquisition of new knowledge (13); (k) expectation of what will happen with the project as a future moment (10); (l) headquarter selection to be part of Explorando Ando (8); and (m) meetings with work teams as a significant moment (6). According to this 13 moments that arose more frequently in the timelines and their count in the descriptive analysis, the following distinctions can be made about each of the participating roles in the process.

Students

The most significant moments for the students, in order of occurrence, were: dream, fear and commitment tree realization (15 mentions), problem search and identification (8 mentions), prototype creation and/or development (14 mentions), and teamwork as a major moment (8 mentions each, this last one as a transtemporal moment). These moments have in common that students had an active and direct participation in each one of them, as well as horizontal with respect to adult roles, “that children talk about the environment to adults, and adults learn” (LT ME1 – E1, 2020). Similarly, these moments are characterized by the fact that they appeal to inquiry and creativity regarding their territories through collaborative work, “the dream, need and goal tree, [through this] we saw that the entire community needs help” (LT SA5 – E2, 2020), or regarding problem search and identification.

Esta etapa me gustó mucho ya que conocí sobre lo que piensan mis compañeros, y estábamos buscando una nueva aventura en la cual íbamos a trabajar mucho para el bien de nuestra comunidad y lo mejor es que estábamos soñando todos juntos un mejor futuro. [I really liked this stage since I learned about what my colleagues think, and we were looking for a new adventure in which we were going to work hard for the good of our community and the best thing is that we were all dreaming of a better future together.] (LT LE2 - E1, 2020).

Community Leaders

For the community leaders, the most significant moments were, in order of occurrence: project’s initial socialization (13 mentions), technological tools delivery (13 mentions), multipurpose classrooms delivery and/or use (13 mentions), and prototype creation and/or development (19 mentions). For the role of leader, made up entirely of female figures except for one case in the municipality of Saldaña (LT SA1 – L1, 2020), the most significant moments are associated with being participants in the project process, “when we found out that our school was a beneficiary of this magnificent project, benefits were explained to us, and how much we would learn from it” (LT LE2 – L1, 2020), while appreciating the educational benefits it generates for students.

Cuando la profesora nos habló sobre el proyecto nos pareció muy importante y me sentí muy afortunada de que hubieran escogido a mi hijo, porque es un proyecto en el que ellos van a aprender a valorar y cuidar el planeta. [When the teacher told us about the project, it seemed very important to us and I felt very fortunate that they had chosen my son, because it is a project in which they are going to learn to value and care for the planet.] (LT ES1 - L1, 2020).

Teachers

In the case of teachers, the most significant moments in chronological order were diploma course participation and completion (14 mentions), creativity team creation (21 mentions), technological tools delivery and multipurpose classrooms delivery and/or use (19 mentions each). Moments that emerge as the most significant ones for teachers are related to their professional practice, since for them technological tools delivery and multipurpose classrooms use are closely linked to their daily work, “los talleres diseñados desde la plataforma para tal fin en aprendizaje y uso de herramientas virtuales para procesos formativos en aula, asesorías preliminares en el uso de los elementos del aula polivalente” [workshops designed from the platform for purposes of learning and using virtual tools for classroom training processes, preliminary advice on the use of elements of the multipurpose classroom] (LT FL4 – D1, 2020), the use of pedagogical tools and the spaces where they carry out their work. Similarly, they recognize that the training they received through the diploma provided a theoretical and methodological support, “me gustó mucho que el proyecto no solo se ha interesado por ponernos actividades o compromisos, sino que nos han brindado la oportunidad de aprender” [I really liked that the project has not only been focused on giving us activities or commitments, but that they have given us the opportunity to learn.] (LT CH3 – D1, 2020), “creo que se consolida una propuesta pedagógica emancipadora para mucho rato” [I believe that an emancipatory pedagogical proposal is consolidated for a long time.] (LT OR4 – D1, 2020).

On the other hand, the choice of creativity teams was in their charge, since they are the ones who know the educational community and are in permanent contact in the territory, “cuando se hizo la convocatoria y que tuvimos más de los estudiantes que requeríamos interesados y cuando convocamos al grupo de padres y líderes y los vi a todos trabajando juntos en una actividad, fue muy edificante” [when the call was made and we had more of the students that were required interested in it, and when we summoned the group of parents and leaders, and I saw everyone working together on an activity, it was very edifying] (LT LE4 – D1, 2020).

Association of Moments and Metamoments

By analyzing significant moments as categories, it can be determined that some of them are closely related to each other. 3 metamoments, them being broad categories of related moments, were identified: reception of spaces and elements, being part of the process and work in/with community. A timeline of the moments and metamoments can be seen on Figure 2.

Figura 2. Timeline moments and metamoments

Metamoment 1. Reception of Spaces and Elements

The first example of this are moment B, technological tools delivery, and moment C, multipurpose classrooms delivery and/or use, which are related both by the amount of mentions they had in total, 45 and 39 mentions respectively, being the second and third the most recognized moments, as by the similarity of thematic, since it could be said that one moment contains another. In other words, at the same time that multipurpose classrooms were handed over to the educational community, technological tools were handed over. However, they arise as two independent moments, and even in some timelines both are mentioned as different moments.

From the union of these two moments a metamoment arises, “Reception of spaces and elements”, named this way because it is characterized by being a moment in which the reception ritual, the novelty and the expectation of all the new possibilities that they represent. This welcoming of spaces and elements can represent both for the future of the project, as well as for the educational processes and for the educational community in general.

20 students mentioned this metamoment (13 moment B and 7 moment C), as well as 26 leaders (13 mentions each moment) and 38 teachers (19 mentions each). In the total combination of these two moments that make up metamoment 1, the reception of spaces and elements was especially a significant milestone for teachers which, in accordance with what was mentioned in the interpretative analysis for those, it is a fact that is related to their professional work in terms of use, support and impact, which they can have through these spaces and elements.

Visitas por parte de los facilitadores del proyecto a las aulas polivalentes de modo presencial, conocimiento de herramientas tecnológicas y seguimiento a proyectos: Acompañamiento de los proyectos desde la virtualidad, charlas, talleres de uso de elementos de aula polivalente desde lo virtual. [Visits by the project facilitators to multipurpose classrooms in person, knowledge of technological tools and monitoring of projects: Accompaniment of the projects from virtuality, talks, workshops on the use of multipurpose classroom elements from virtual environment.] (LT FL4 – D1, 2020)

For students and leaders it can be interpreted as the innovative impact that having access to tools and classrooms which offer various possibilities for their educational and community processes can have, “cuando le entregaron a los niños el aula polivalente se pusieron muy felices; ahorita estamos esperando poder construir el prototipo con los equipos de creatividad y el apoyo de las profesoras de Explorando Ando” [when the children were given the multipurpose classroom they were very happy; right now we are waiting to be able to build the prototype with creativity teams and the support of teachers of Explorando Ando] (LT CH5 – L1, 2020), and “la entrega de los elementos del aula como tabletas, sillas, mesas, porque nos están ayudando a nosotros como estudiantes de la vereda a avanzar en tecnología y nos gustaron muchos los elementos” [classroom elements delivery such as tablets, chairs, tables, because they are helping us as students from the village to advance in technology, and we loved the elements a lot] (LT FL4 – E1, 2020).

Metamoment 2. Being Part of the Process

The metamoment “Being part of the process” emerges from moment F, project’s initial socialization with 30 mentions, and moment L, headquarter selection to be part of Explorando Ando with 6 mentions, which arise jointly because they have in their essence the expectation of starting a new process in educational communities, as well as the courage and pride of having been chosen from so many headquarters and members that are part of the creativity teams.

Regarding teachers (17 total mentions of the metamoment, 13 mentions of moment F and 4 mentions of moment L), this meta-moment can be related to the crucial role they have played throughout the project, especially at the beginning, when being them the ones with the closest connection in the territory, they acted as liaison between project professionals and educational institutions.

Fue cuando el proyecto llegó a la escuela, pues saber que era un proyecto que iba a integrar a los niños, que iba a manejar la creatividad y la parte social, la comunidad y la parte científica, eso fue una motivación muy bonita y los niños estaban muy entusiasmados, pienso que ese fue uno de los momentos como más chéveres (…). [It was when the project arrived at school, because knowing that it was a project that was going to integrate children, that it was going to handle creativity and the social aspect, the community and the scientific aspect, that was a quite nice motivation and children were thrilled, I think that was one of the coolest moments (…).] (LT LE2 – D1. 2020)

For students (5 total mentions, 4 for moment F and 1 for moment L) and leaders (14 total mentions, 13 and 3 for each moment respectively), as mentioned above, it was all about assessing educational advantages and transformations that the process may generate, “cuando nos presentaron el proyecto y los beneficios que traía para la comunidad, en ese instante supe los beneficios y decidí participar en él” [when the project and benefits it would bring to the community were presented to us, at that moment I realized the benefits and decided participate in it] (LT OR1 – L1. 2020), and:

[Desde] el inicio del programa con la profesora, el tenernos en cuenta como estudiantes para identificar problemas o falencias en nuestro alrededor. La atención y dedicación de ello hace que seamos activos y recursivos en el momento de crear soluciones, con el árbol de necesidades y sueños. [[Since] the beginning of the program, the teacher took us into account as students to identify problems or weaknesses around us. The attention and dedication of this makes us active and recursive when creating solutions, with the need and dream tree.] (LT AR1 – E1. 2020)

Metamoment 3. Work in/with Community

“Work in/with the community” emerges from moment H, teamwork as a major moment, and moment M, meetings with work teams as a significant moment, the first mentioned 15 times and the second 6 times in total. This is conformed by having as its essence the importance of working together and all the processes that are carried out there, such as listening to the other, socializing, knowing and expanding the possibilities regarding a common objective, which in this case corresponds to what each creativity team intends to do in their projects.

This metamoment, especially for the students (9 total mentions, 8 for moment H and 1 for moment M), was a moment that stands out within their mentions, insofar as they associate it with the game, horizontal participation and the discovery of aspects of their reality that they understand, can transform, “cuando [nos] integramos y empezamos a explorar temas y vocabularios desconocidos, sobre aspectos que jamás habíamos imaginado que podíamos cambiar” [When [we] integrate and begin to explore unknown topics and vocabularies, about aspects that we had never imagined we could change.] (LT ES3 – E1, 2020); “el compartir con mis compañeros sobre las ideas creativas del proyecto y de lo que nosotros hacemos en la institución con los profesores” [Sharing with my colleagues about the creativity ideas of the project and what we do in the institution with the teachers.] (LT FL4 – E1, 2020); and “compartir con mis compañeros, respetar, expresar sentimientos e ideas y tener nuevos conocimientos” [Sharing with my classmates, respecting, expressing feelings and ideas, and acquiring new knowledge.] (LT ME4 – E1, 2020).

Regarding leaders (7 mentions, 4 for moment H and 3 for moment M) and teachers (5 mentions, 3 for H and 3 for M), as one of the latter mentions, related to the work with creativity teams and accompanying pedagogues, “estos encuentros ilustran la importancia y aplicación de los aprendizajes colaborativos y cooperativos” [These meetings illustrate the importance and application of collaborative and cooperative learning.] (LT OR4 – D1, 2020); in other words, when “Work in/with community” is highlighted, it is because of the integrating characteristic and directed towards the common good that it possesses.

[El] trabajo con el proyecto de medio ambiente y una aplicación en la que la comunidad convoca lo que se ha trabajado con Explorando Ando y tiene por nombre kjcxacxanas- fortaleciendo. La comunidad ha [venido] trabajado con ánimo al conocer los beneficios que conseguiremos trabajando unidos. [[The] work with the environment project and an application in which the community summons what has been worked with Explorando Ando and is called kjcxacxanas - strengthening. The community has [been] working with courage knowing the benefits that we will achieve by working together.] (LT PL5 – D1, 2020)

Discussion and Conclusions

The relevance of ASCyT processes that start and link the contexts and specific territorial needs is highlighted as a local development strategy, of ownership and sustainability of intervention and of social appropriation initiatives, as well as the relevance of processes that favor the linking of the educational community with the various social actors in the context, students, teachers, community leaders, parents, institutional directors and others.

In contrast to the above, the absence of CTeI in urban and rural contexts of the department of Tolima is critically evident. In a positive way, it allows us to see the relevance for communities of access to technological equipment for connectivity and pedagogical alternatives. In a negative way, it shows a great void, a reflection of social inequality in the department of Tolima-Colombia, regarding access to these same media.

The use of participatory methodologies such as the Systematization of Experiences in contexts of community work and with broad links with rural communities is highlighted. The use of the Timeline as an instrument to access the elaborations of significant experiences of the participants of social processes is similarly highlighted, because it is an instrument of easy mastery for boys, girls, community leaders and teachers, as well as allowing the construction of subjective and collective knowledge based on experiences of the same nature. Likewise, the methodological flexibility around the adaptation of instruments in remote and virtual environments that allow a wide and clear dissemination of them, according to the means available to the participants, is enhanced. There is much for thought on the use of virtual research methodological strategies for social processes of dialogue and co-construction of knowledge. From this experience, the potential to favor a greater geographical scope in the information gathering processes is evident.

In order to be faithful to a participatory approach with virtual tools, more time and attention must be devoted to the preparation of the instrument and the environment, as well as during the interaction. During the design of the instrument and the environment we worked on clarifying the instructions in a language that was friendly in its expression and simple in its comprehension, the objectives were well defined and delimited in the data collection spaces, the instruments were designed thinking of an other person who has a different experience, whatever it may be, of interaction with the virtual or remote work. At the same time, all the tools were tested before being implemented. Finally, the relationship between time and number of participants must be considered, as the perception of time in virtuality can also vary. It is important to remain calm if there are internet failures, or if you have to repeat an instruction due to network instability and, above all, to build and share confidence to face with sensitivity and curiosity a new scenario of social interactions in research. During the meeting, it is important to try to work as a team, divide tasks of accompaniment, coordination and chat management, as well as management of support tools. In face-to-face fieldwork, do not rely on the recording you leave of the meeting. Take notes and write questions, doubts and insights in your researcher's log.

The clearest limitation of these media is evidenced in the absence of the complete human experience, that is, the body as a great absentee, which involves the difficulty to read interactions, expressions, reactions, the difficulty to record the experience in multiple dimensions or to embrace the experience and the input of each one in the conversation or interview, and the limits to interact and share who we are in spaces limited by a screen. At the same time, it is interesting to wonder about the reception of participants who, through this virtual means of data collection, felt more comfortable and confident, preferred to deliver the exercise without questions or dialogues, or felt comfortable with the distance of the virtual medium, perhaps as a way of feeling protected, not feeling tested or questioned in their own experience, this potential will have to be carefully explored.

It is important to remember that participation is the main purpose and to not abandon it due to lack of time or network failures. Currently there are different free platforms to work with virtual collaborative boards and questions in real time, and above all tools, it is important to remember that this is also an environment to cultivate trust, empathy, listening, care for the other, social criticism, presence and accompaniment.

References

Acevedo, J. (2008). Sistematización de experiencias proyecto: asociación de medios de comunicación ciudadanos y comunitarios de Medellín. – LA REDECOM – Federación Antioqueña de Organizaciones no Gubernamentales. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de la Economía Solidaria. http://centroderecursos.alboan.org/ebooks/0000/0925/6_ACE_SIS.pdf

Agudelo, A. y Jiménez, L. (2017). Diseño Metodológico proyecto Diplomado Diálogo de Saberes para la Investigación y la Sistematización de Conocimientos Locales. Experiencias Vivas. Fundación Confiar.

Barbosa-Chacón, J., Barbosa-Herrera, J. y Rodríguez Villabona, M. (2015). Concepto, enfoque y justificación de la sistematización de experiencias educativas. Una mirada “desde” y “para” el contexto de la formación universitaria. Perfiles Educativos, 37(149), 130–149. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/132/13239889008.pdf

Belotti, A., Caffaratto, A., Filippa, S. y Sarmiento, G. (2005). La integración escolar de niños con síndrome de Down. Un camino hacia la escuela inclusiva. Brujas.

Bhatt, S., Kala., S. y Kalisch, A. (2014). Case Study. Systematisation: learning from experiences of community-based adaptation projects in India. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 10(3), 88–100. http://journal.km4dev.org/

Carrillo, A. y Cordero, D. (2017). La sistematización como investigación interpretativa crítica. El Búho Ltda. https://www.academia.edu/37500472/La_sistematizaci%C3%B3n_como_investigaci%C3%B3n_interpretativa_cr%C3%ADtica

Castañeda-Meneses, P. y Salamé-Coulon, A. (2021). Sistematización y Trabajo Social en Chile. El largo y sinuoso camino. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica. (2015). Los caminos de la memoria histórica.CNMH. http://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/descargas/informes2015/caminos-para-la-memoria/caminos-para-la-memoria-cartilla-participacion-victimas.pdf

Chimbo, J. (2019). El trabajo social y la comunicación comunitaria como estrategia de organización política para el fortalecimiento de la identidad y la recuperación de la memoria en la comunidad Santa Catalina de Salinas Imbabura en el periodo abril – agosto 2019. [Tesis de licenciatura en Trabajo Social]. Universidad Central del Ecuador. http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/bitstream/25000/20311/1/T-UCE-0013-CSH-150.pdf

Chiner, E. (s. f.). Investigación descriptiva mediante encuestas.Universidad de Alicante. https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/19380/34/Tema%208-Encuestas.pdf

Chiner, E. (2011). Las percepciones y actitudes del profesorado hacia la inclusión del alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales como indicadores del uso de prácticas educativas inclusivas en el aula. [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad de Alicante. https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/19467/1/Tesis_Chiner.pdf

Chingaté, N. (2009). Democratización del conocimiento científico tecnológico en Colombia. Papel Político, 14(2), 393–408. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/papel/v14n2/v14n2a03.pdf

Chuchullo, J. y Cáceres, E. (2015). Recopilación y sistematización de saberes durante el periodo 2010 –2012, en la Institución Educativa N° 56043, Machacmarca, Tinta. [Tesis de especialidad]. Universidad Nacional de San Agustín. http://repositorio.unsa.edu.pe/handle/UNSA/5431

Cipriano, A. (2008). La apropiación social de la ciencia: Nuevas formas. Revista CTS, 10(4), 213–225. https://minciencias.gov.co/sites/default/files/ckeditor_files/apropiacion-nuevasformas.pdf

Colciencias (2010). Estrategia Nacional de Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación. Colciencias.

Cole, M. y Scribner, S. (1977). Cultura y pensamiento: Relación de los procesos cognoscitivos con la cultura. Limusa.

Consejo de Educación Popular de América Latina y el Caribe. (2012). Quiénes somos. Sito web del CEAAL. http://www.ceaal.org/v2/cquienes.php

Convenio Andrés Bello (2013). V Reunión en Apropiación social de la ciencia, la tecnología y la innovación de los países CAB«. http://convenioandresbello.org/cab/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/V_Reunion_Apropiacion_Social_Ciencia_y_Tecnologia.pdf

Corredor-Sotelo, Y. y Fuentes-Fuentes, J.(2021). La memoria transformadora como estrategia de intervención profesional en los procesos de reconciliación social: comprensión a partir de mujeres campesinas, excombatientes y jóvenes en Manizales, Colombia. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10546

Cuello-Lacoutire, L. y Jaramillo-Jaramillo, J. (2021). Sistematización de la experiencia Reconocimiento de los derechos humanos del adulto mayor en dos familias residentes en Cali y Valledupar (Colombia). Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10565

De Sousa, B. (2010). Descolonizar el saber, reinventar el poder. Trilce.

Decreto 585. (1991, 26 de febrero de ).Diario Oficial (39702). https://www.redjurista.com/Documents/decreto_585_de_1991_presidencia_de_la_republica.aspx#/

Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Colciencias (2010). Estrategia Nacional de Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación. https://minciencias.gov.co/sites/default/files/ckeditor_files/estrategia-nacional-apropiacionsocial.pdf

Díaz, A. (2019). Nuevos ambientes educativos en el aprendizaje de las Ciencias Sociales. Sistematización de una experiencia didáctica en Educación Secundaria en Nicaragua. Revista Científica de FAREM-Estelí, (30), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.5377/farem.v0i30.7885

Echeverry-Velásquez, M. y Prada-Dávila, M. (2021). La sistematización de experiencias, una investigación social cualitativa que potencia buenas prácticas de convivencia y gobierno. La experiencia de un conjunto residencial multifamiliar en Cali, Colombia. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 151–176. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10595

Esteban-Carbonell, E. y Olmo-Vicén, N. (2021). La sistematización de la intervención como metodología de investigación en Trabajo Social. Importancia práctica y teórica de la fase de recogida de datos en la intervención social según experiencia del Programa de Apoyo a las Familias en Zaragoza, España. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.8857

Estupiñán H., Mosquera Y., Márquez J., Mondragón Pérez L. y Vitale L. (2014). Sistematización, análisis y promoción de procesos de apropiación social de CTI en el marco de la investigación participativa de organizaciones sociales en tres diferentes contextos culturales y ambientales de Colombia. http://www.ecofondo.org.co/articulo.php?id=146

Giménez, G. (2005). Territorio e identidad. Breve introducción a la geografía cultural.Trayectorias, 7(17), 8–24. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/607/60722197004.pdf

Falkemback, E. y Torres-Carrillo, A. (2015). Systematization of Experiences: A Practice of Participatory Research from Latin America. En H. Bradbury (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Action Research (pp. 74–80). SAGE. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473921290.n8

Goldar, M. R. y Chiavetta, V. (2021). Aportes y desafíos de la Sistematización de experiencias en el Trabajo Social y la extensión crítica. Apuntes y reflexiones desde la perspectiva de la Educación Popular. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10648

Guba, E. (1990). The paradigm dialog.SAGE.

Halbwachs, M. (2004). Los marcos sociales de la memoria. Anthropos.

Hernández-Sampieri, R., Fernández, C. y Baptista, M. d. (2014). Metodología de la investigación(5 ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Henao, L., Mazorco-Salas, J., Pedreros, N., Ruíz, R. y Varón, L. (2022). Sistematización de una estrategia de apropiación social de la ciencia, tecnología e innovación: Promoción del pensamiento crítico en niños, niñas y jóvenes en instituciones educativas del Tolima. Unibagué.

Henao, L., Mazorco-Salas, J. y Ruiz, R. (2020). Sistematización e implementación de una estrategia de apropiación de CTeI para promover el pensamiento crítico en los estudiantes. En E. Serna (Ed.), Revolución en la Formación y la Capacitación para el Siglo XXI (pp.112–123). Instituto Antioqueño de Investigación. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Edgar-Serna-M/publication/346026666_Revolucion_en_la_Formacion_y_la_Capacitacion_para_el_Siglo_XXI_Vol_I_ed_3/links/5fb6b81ea6fdcc6cc64be039/Revolucion-en-la-Formacion-y-la-Ca-pacitacion-para-el-Siglo-XXI-Vol-I-ed-3.pdf

Herout, P. y Schmid, E. (2015) Case study. Doing, knowing, learning: systematization of experiences based on the knowledge management of HORIZONT3000. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 11(1), 64–76. http://journal.km4dev.org

Honor, Y. (2015). Habilidades de indagación científica promovidas por el programa “Tierra de Niños” en la I.E. 50482-Cusco. Sistematización de la experiencia educativa 2009-2014. [Tesis de maestría]. Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. http://repositorio.upch.edu.pe/handle/upch/92

Jara, O. (2012). Sistematización de experiencias, investigación y evaluación: Aproximaciones desde tres ángulos. Revista Internacional sobre Investigación en Educación Global y para el Desarrollo, (1), 56–70. http://educacionglobalresearch.net/wp-content/uploads/02A-Jara-Castellano.pdf

Jara, O. (2017). Sistematización de experiencias: Práctica y teoría para otros mundos posibles. CINDE. http://www.cinde.org.co/userfiles/files/Novedades.pdf

Jara, O. (2018). La sistematización de experiencias: Práctica y teoría para otros mundos políticos. CINDE. https://repository.cinde.org.co/visor/Preview.php?url=/bitstream/handle/20.500.11907/2121/Libro%20sistematizacio%CC%81n%20Cinde-Web.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Jiménez, L. y Agudelo, A. (2020). desafíos en la coproducción de conocimientos desde el diálogo de saberes y la sistematización de experiencias: una perspectiva política. pluralismos epistemológicos: nuevos desafíos de la investigación y la sistematización de experiencias. https://www.academia.edu/41789165/desafi_os_en_la_coproducci%c3%b3n_de_conocimientos_desde_el_di%c3%a1logo_de_saberes_y_la_sistematizaci%c3%b3n_de_experiencias_una_perspectiva_pol%c3%adtica

Ley 29 de 1990. (1990, 29 de febrero). Por medio de la cual se dictan disposiciones para el fomento de la investigación científica y el desarrollo tecnológico y se otorgan facultades extraordinarias.

Llanos-Hernández, L. (2010). El concepto del territorio y la investigación en las ciencias sociales. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo, 7(3), 207–220. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/asd/v7n3/v7n3a1.pdf

Manfred, M. (1993). Desarrollo a escala humana. Conceptos, aplicaciones y algunas reflexiones. Nordan-comunidad.

Marín, S. (2012). Apropiación social del conocimiento: Una nueva dimensión de los archivos. Revista Interamericana de Bibliotecología, 35(1), 55–62. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=292/29210112

Ministerio de Educación (2019, 31 de julio). El convenio Andrés Bello. https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/portal//357392:El-Convenio-Andres-Bello

Mora-Lemus, G. (2021). Construcción de subjetividades epistemológicas-políticas de profesoras y profesores de Investigación social en una universidad privada y confesional en Bogotá. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención Social, (31), 177–199. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10678

Morales, A. y Quintero, N. (2015). Un viaje por la sistematización de experiencias a través del proyecto comunicando. [Tesis de maestría]. Universidad Santo Tomás. https://repository.usta.edu.co/handle/11634/520

Quispe, F., Felipa, L., Mancilla, M., Acarapi, G. y Navia, E. (2018). Sistematización: Aprender haciendo - enseñar produciendo. Experiencia de implementación del PSP en la Unidad Educativa “Urus Andino” de Chipaya. Fundación Machaqa Amawta. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WCf13VH7kW9ZsTQauI1f9pExm4Z-jgql/view

Red Alforja (s. f.). Historia. Sitio web de Red Alforja. Consultado el 12 de enero de 2022 en https://redalforja.org.gt/historia/

Ricœur, P. (2004). La memoria, la historia, el olvido. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Ricoeur, P. (1996) Sí mismo como otro. Siglo XXI.

Rivera, L. y Valencia, N. (2016). Sistematización de una experiencia docente del área rural en institución educativa pública del municipio de Quinchía. Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira. http://repositorio.utp.edu.co/dspace/handle/11059/7025

Ruiz-Lozano, R. (2019). Políticas y prácticas pedagógicas inclusivas para la generación de una cultura inclusiva. Grupo de Investigación en Educación Social. Universidad del Tolima. http://repository.ut.edu.co/bitstream/001/3014/2/POLITICAS_Y_PRACTICAS_PEDAGOGICAS_CONTENIDO_23_10_2019.pdf

Sepúlveda-Hernández, E. (2021) Sentipensar la pandemia COVID-19 desde la sistematización de la experiencia en Trabajo Social: reflexiones del profesor Oscar Jara Holliday. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención Social, (31), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10653

Sequeda, S. (2017). Caracterización de una experiencia de interacción educativa dialógica de apropiación social de la ciencia y la tecnología, con niños en edad temprana, en ámbitos no formales, a partir de la sistematización del Club Pequeños Exploradores de Maloka.Revista Aletheia de Desarrollo Humano, Educativo y Social Contemporáneo, 9(1), 116–137. https://aletheia.cinde.org.co/index.php/ALETHEIA/article/view/383/237

Torres-Carrillo, A. (2021). Hacer lo que se sabe, pensar lo que se hace. La sistematización como modalidad investigativa.Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención social, (31), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i31.10624

Torres-Carrillo, A. (2010). Generating Knowledge in Popular Education: From Participatory Research to the Systematization of Experiences. International Journal of Action Research, 6(2-3), 196–222. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-414151

V Foro de Apropiación Social de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación. (2014). Memorias. Colciencias. http://repositorio.colciencias.gov.co/handle/11146/790

Vence, L. (11 de febrero de 2014). Sistematización de experiencias significativas. Todos a aprender. Atlántico. https://es.slideshare.net/PTAaTLANTICO/sistematizacin-de-experiencias-Significativa

Aknowledgments

Thanks to each participant from the distant and difficult contexts of Tolima-Colombia.

About the authors

Julio Eduardo Mazorco Salas (julio.mazorco@unibague.edu.co) is a PhD student in Local Development and International Cooperation at Universidad Politécnica de Valencia; Master in Education by Universidad de los Andes, Colombia, and Mater in Communitary Mental Health by Universidad del Bosque, Colombia. Graduated in Philosophy by Universidad de Ibagué, Colombia, and in Psychology by Universidad de San Buenaventura, Colombia. (ORCID 0000-0002-2008-4382).

Laura Yamile Henao Morales (laura.henao@unibague.edu.co) has a Master in Territory, Conflict and Culture by Universidad del Tolima. Specialist in Childhood, Culture and Development by Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. (ORCID 0000-0002-4801-0561).

Robinson Ruiz Lozano (rruizlo@ut.edu.co) has a PhD in Educational Sciences by Universidad del Tolima-Rudecolombia, Colombia. Master in Popular Education and Community Development by Universidad del Valle, Colombia. Specialist in School Guidance by Universidad del Quindío, Colombia. (ORCID 0000-0002-9235-2331).

Liz Andrea Varón Matha (lizandrea.vm2506@gmail.com) is Graduated in Design by Universidad de Ibagué, Colombia. (ORCID 0000-0001-5640-9858).

Recibido: 27/05/2021

Aceptado: 21/01/2022

Cómo citar este artículo

Mazorco, J. E., Henao, L. Y., Ruiz, R. y Varón, L. (2022). Systematization of an Educational Experience of Social Appropriation of Science, Technology and Innovation:The Collective Memory built with Participatory Virtual Tools. Caleidoscopio - Revista Semestral de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 24(46). https://doi.org/10.33064/46crscsh3221

Esta obra está bajo una

Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional

Usted es libre de compartir o adaptar el material en cualquier medio o formato bajo las condiciones siguientes: (a) debe reconocer adecuadamente la autoría, proporcionar un enlace a la licencia e indicar si se han realizado cambios; (b) no puede utilizar el material para una finalidad comercial y (c) si remezcla, transforma o crea a partir del material, deberá difundir sus contribuciones bajo la misma licencia que el original.

Resumen de la licencia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.es_ES

Texto completo de la licencia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode